Story of Blood

Assistance with curiosity

Recently, re-reading the first volume of Mircea Eliade’s A History of Religious Ideas (the one which covers the period from the Stone Age to the Eleusinian Mysteries), I found myself missing the author, his encyclopedic knowledge and deftness in analogy and synthesis. Despite the breadth of his existing work, I wanted to have him at my shoulder to make me aware of new stories and to point out connections within the vast web of human myths and stories.

Eventually I settled (as we seem to more and more) for that inert facsimile of the never-resting mind: the encyclopedia, perhaps with hyperlinks to stand in for analogies. During this search I happened upon Stith Thompson’s massive labour of love, the Motif-Index of Folk-Literature which contains 46230 distinct motifs: the building blocks of “Folktales, Ballads, Myths, Fables, Mediaeval Romances, Exempla, Fabliaux, Jest-Books and Local Legends.” While the index has its limitations for research purposes,1 it serves my initial intent to give a broad, impressionistic sketch of themes across cultures and time.

It turns out that one can do some web-scraping and tidying up to arrive at a working dataset for these motifs. As for methods, I’m starting out pretty basic. After a few forays applying topic modeling with results which strayed too far from the types of nuanced categories I had hoped for, I settled on simply tagging keywords using regular expressions: a bit more work, but more useful output. Not the most elegant approach,2 as the grouping of some motifs shows. Nevertheless I’ve resisted re-classifying the initial sketch, sticking (for now) with the vividness of first impressions rather than an unassailable classification system.

So… what to explore?

Why blood?

The first thing I wanted to explore was blood. Blood is at the heart of our hopes and fears, a single substance with veins rooted in life and death. Red hands colored in ochre to resemble blood have been found at Paleolithic sites throughout the world. We have analyzed blood’s chemical composition and use it to quantify our wellness with HbA1c levels and lab workups. Alongside our increasing application of this scientific knowledge to develop treatments, blood continues to be used ritually as well. Around the world, millions of Christian believers gather each week to drink the blood of God as part of the millennia-old rite of the Eucharist. Some may take it as a ‘mere symbol’ and some as a mysterious reality, yet the action is rooted deep within our collective history.

Blood is also a figure for our greatest fears: an emblem of life so strong that the loss of it is the harbinger of danger and death. The horror-movie section of Netflix provides ample modern-day examples of this particular connotation. Despite its ubiquity, blood has not become a safe or cliche metaphor; precisely because it is not a metaphor. It is in us.

What is ‘in our blood’ is not merely hemoglobin or lipoproteins, but an entire history of resonances, of stories and ideas about ourselves which color the substance coursing through our veins.

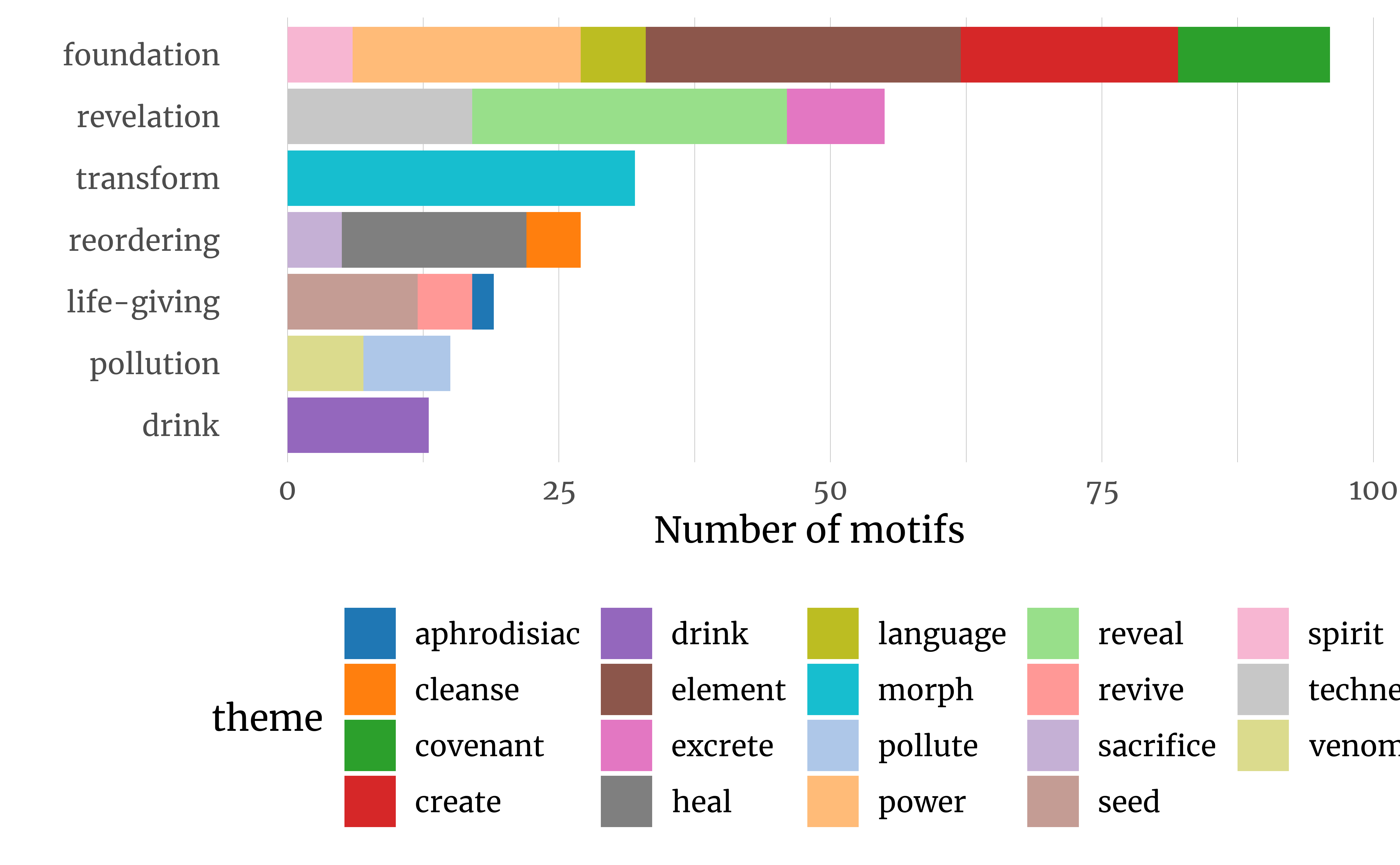

Searching the Thompson Motif Index for ‘blood’ or ‘bleed’, we find 380 entries. By flagging motifs with keywords which correspond to identified themes, I ended up with a reduced set of 257 entries categorized by theme.3 Gathering these 19 themes into 7 broader groups yielded the categories used in the discussion below.

By reviewing and classifying the motifs as themes, then clustering those themes into more abstract groups, several characteristics of blood impressed themselves on me. There are certainly other constellations which might be traced among these points but these are a start. Based on the motifs in this index, blood is depicted:

- as a foundational element of the cosmos,

- as a life-giving material, vivifying individual beings

- as an impetus for reordering, reorienting broken or hurt beings back to the cosmic foundation

- as an agent of revelation, showing the true nature of objects, people, or situations

- as an agent of transformation or metamorphosis, altering physical form

- as a drink taken to obtain one of the characteristics noted above

- as a pollutant (in contradiction to the theme of reordering noted above)

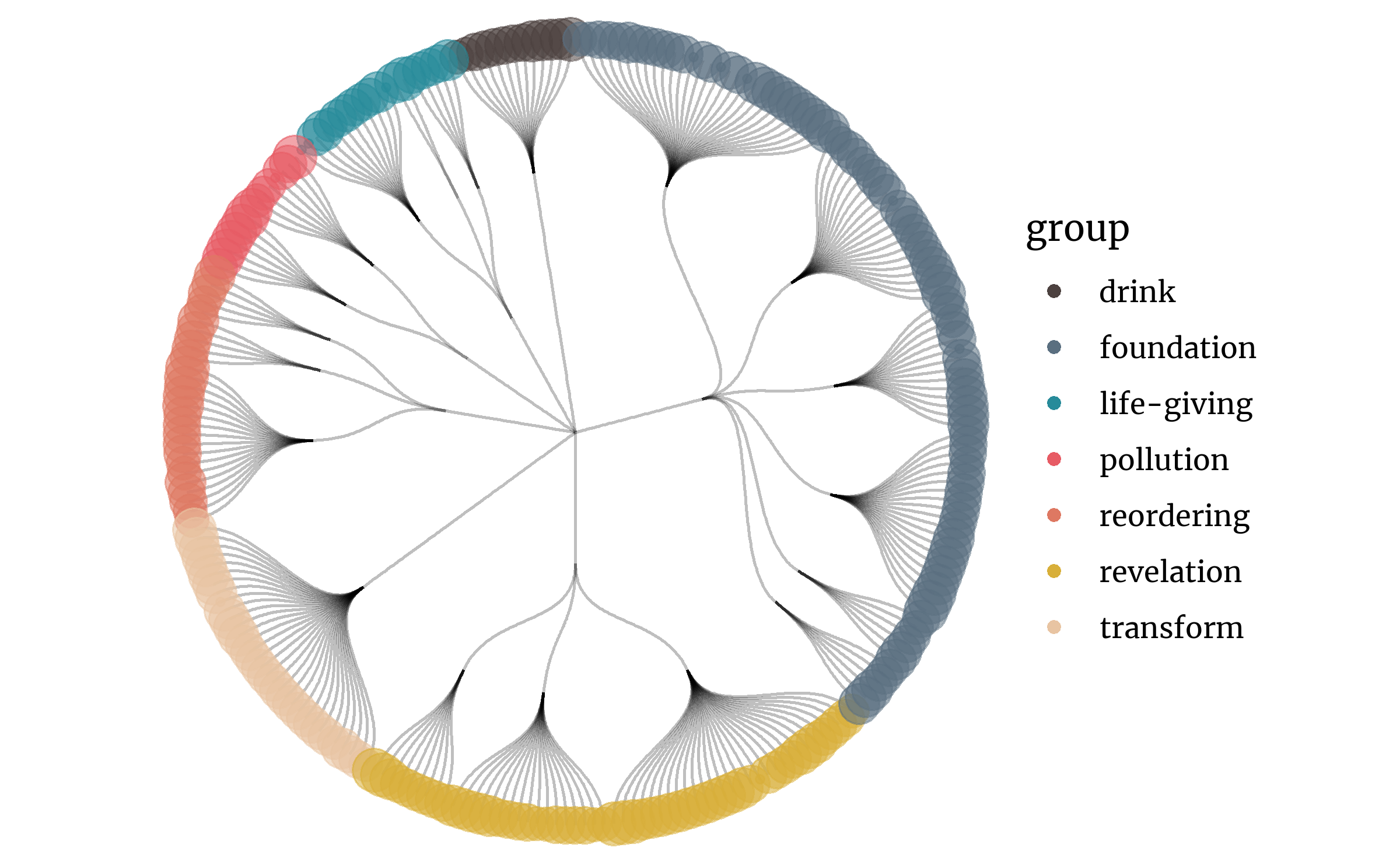

Nearly all of these groups have distinct themes congealed within them, so it is worth dwelling on each in greater detail as well as providing illustrations of the variety of motifs within each group. The overall structure of these groups, subgroups, and motifs is shown below as a circular network:

Each set of branches from the trunk of this network is briefly discussed and presented for exploration in a section below, to give a sense of the diversity of myths and stories represented.

Cosmic Foundation

The first and largest set of themes which clustered together were those about the essence of blood. Vital and numinous, blood seethes with the creative power of life itself. It is related to and in some instances constitutes the substance of the soul, which has previously been defined quite differently than our current usage. For the Greeks, the soul was not merely a wisp but the patterning power which governed the unfolding and development of the body. Blood carries this connotation in motifs which connect it with soul/spirit, with the basic elemental forces of the world, or with the initial creation of the cosmos (i.e. cosmogonic myths).

You can expand the nodes of the diagram below and browse the motifs in this broader set of themes.

The use of the word ‘cosmos’, as distinguished from ‘universe’, is intentional here. The world which these myths conjure is personal and harmonious, while capricious and eerie.

Additional themes in this group illustrate blood’s foundational nature, such as its use in endorsing contracts and covenants. Since blood is a deeper power than the individual interests of those making the deal, it can be relied upon to enforce agreements, allowing them to rest on a force which under-girds particular biases.

Also included here are more generic references to the power of blood, often characterized as magical: attempts to harness its numinous vitality to serve human purposes.

Related to this raw energy, and tied to the notion of ‘soul’ as a patterning power, are motifs which depict blood as holding knowledge, particularly language. In some stories, drinking the blood of animals gives understanding of their language.4 It can also return speech to those who had been unable to speak.5 Blood induces speech not simply by healing the speech organs but by imparting knowledge of language itself: the patterning power by which creation was spoken or sung into being6 and which continues to course through living blood. Language here is an indication of understanding, and the vitality of blood may be understood not as a blind force but as a conscious, one might even say personal, energy. This association almost seems a foreshadowing of the discovery of DNA, the inherence of patterning soul and word within individual creatures, folded up in miniature as a word, a sequence of symbols.7

It is this set of intuitions about the cosmic essence of blood which serve as the basis for nearly all other motifs. Because of this essence, blood is has an active role in creating specific beings as well…

Life-Giving

Blood is a seed, causing trees to sprout from the ground where it is spilled8 or a mandrake to rise up at the foot of the gallows9. Falling from us as we die, it signals that the pulse of life transcends our particular existences. People are conceived or born from blood10, and this potency leads by association to its use as an aphrodisiac.

With this role in initiating life, it is no surprise that blood is also able to re-kindle it: bringing to life what has died, such as in the French fable of the pelican reviving its young11 which draws on earlier Christian symbolism.

As has likely become obvious already, the membranes between these categories are porous and allow for commerce. The power of blood to bring back to life is echoed in its use for healing and renewal, as collected in the theme of…

Reordering

The vitality of blood seems to wash away time, erasing the decay of wounds or sickness. One can bathe in blood and be cured of disease,12 use blood to restore sight,13 or even (somewhat paradoxically) have a wound healed by its own blood.14 Bathing in blood also has a cleansing function, as in the range of motifs grouped in the category titled cleanse.

The nature of the connection between cleanness and health in these themes is unclear, and it would be a mistake to anachronistically apply our current notions, informed by germ theory. Earlier conceptions of what was “clean” and ritual purity did not necessarily have to do with an absence of germs but with the proximity to situations or materials associated with impurity.15

Motifs are also included in this group which refer to the use of blood as a ‘sacrifice’, a literal ‘making sacred’ which restores the cosmos.

Revelation

Perhaps because it is a deep substance of the world, blood is able to reveal what is behind initial appearances. It is a medium of communication with transcendent reality, allowing individuals to receive evidence beyond what their limited vantage allows for. Yet rather than inducing hallucinatory ‘otherworldly’ intuition, it often has the effect of producing disenchantment and sobriety.16

When it reveals disobedience or wrongdoing, blood serves as a sign of judgment. Keys and eggs become bloody as a sign of disobedience,17 and murderers are found out by blood springing miraculously from themselves or their victims, or bubbling when they wander near.18

When blood comes from certain inanimate objects, it reveals the life or more substantial reality of those objects. In Irish myths, a shrine bleeds to identify its living connection with reality,19 and a desecrated altar also bleeds to remind people of the continued power of reality beyond that impure act.20

Transformation

Similar to the motifs related to cleansing and healing, where blood brings about a change in the physical state of the person to whom it is applied, there are also stories in which blood transforms a person, animal, or object into something else, or in which blood itself is turned into one of these. So, while blood itself is acknowledged as elemental and as connected with the unfolding of life, it is not necessarily beholden to any specific instance of that life.

It can change the structure of one object or being into another, because it is deeper than any of those provisional forms. The use of blood in covenants, referenced above, also relies on this understanding of the substance.

Pollution

Blood gives life but we see it most often when life seeps from us, so it is associated both with vitality and with the loss of that vitality in death. Often the things associated with death become taboo: these are objects or substances which confer ritual impurity in a religious ceremony or otherwise render someone unclean if they have come into contact. Even the ground can become unclean when it comes into contact with menstrual blood.21 Such an interpretation underlies the rules set out in Leviticus, which keep participants from having contact with substances associated with death or procreation.22 This taboo on blood indicates how thin is the membrane between life and death, how mingled.

Other motifs grouped here refer to the blood of various animals thought to be venomous: snakes, lions, toads, bears, and of course dragons.

Drink

When motifs were not explicitly tied to the reasons why people were drinking blood (e.g. to transform themselves, or make a pact, etc.), I classified them in a separate category.

While the motive for drinking blood may not be clear in these instances, the act itself is of interest. Other means of applying blood (e.g. baths) are present and mentioned above. The ingestion of another creatures blood, the taking of external life into one’s own body through the mouth, the same route by which the body accepts all other nourishment, is so central to myth and particularly to Christian practice that it is worth dwelling upon.

In reviewing the motifs associated with this use of blood, however, we find mostly negative uses: witches sucking blood, ogres drinking the blood of their victims, and similar tales.

Admittedly, I had thought to find ritual uses of drinking blood in this group, yet the motifs shown here illustrate why early Christian practice was so often seen as appalling to those who heard about it. This association of blood, one liquid life-force, with water or other drink which are the practical sustenance of life for all humans or other creatures, draw an analogy between blood and nourishment. Since these do not usually involve the drinking of one’s own blood, it is nourishment through taking the blood of another into oneself. In the Eucharist, where the blood of sacrificed creatures is replaced by the blood of God, source of Life itself.

See d’Huy, J., Le Quellec, J. L., Berezkin, Y., Lajoye, P., & Uther, H. J. (2017). Studying folktale diffusion needs unbiased dataset. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(41), E8555-E8555.↩︎

In order to apply a single theme to a given motif which may have matched multiple search criteria, I used a

case whenstatement which explicitly chooses an order of importance and individual motifs to the first group for which it meets criteria. A refined approach might be to use the gamma score from topic model output, if those could be made to generate useful groupings. Then a given motif could be associated more or less strongly with multiple themes.↩︎Note that a substantial number of motifs (n = 123) including the words ‘blood’ or ‘bleed’ were not grouped using the search criteria applied. Most of these have to do with tales such as those involving ogres visiting violence on their victims, etc.↩︎

See D1301.2 Drinking Blood Teaches Animal Languages; (Cf. †D1041.) –**Scott Thumb; Panzer Sigfrid 281 s. v. “Vogelsprache”. –Icelandic: Völsungasaga 45, Boberg.↩︎

As in D1507.6 Saint’s Blood Restores Speech; (Cf. †D1003.) Irish myth: Cross.↩︎

e.g. in the Genesis account or the Rg Veda↩︎

I feel tempted to beckon toward the field of biosemiotics, to point out the beautiful forays of thought occurring there.↩︎

See motif F979.12 Trees Spring Up From Blood Spilled On Ground; (Cf. †D1003.) Irish myth: Cross.↩︎

See motif A2611.5 Mandrake From Blood Of Person Hanged On Gallows; (Cf. †A2664.) –**Starck Der Alraun; Taylor JAFL XXXI 561f.; Penzer III 153.; Fb “alrunerod” IV 10a.↩︎

Various motifs, such as T541.1 Birth From Blood; Greek: Frazer Apollodorus I 5 n. 4, Fox 6, 262; Philippine (Tinguian): Cole 15, 63, 71, 124., or T541.1.1 Birth From Blood-Clot; Hatt Asiatic Influences 80ff.; Oceanic: Dixon 109, 251 n. 25; Mono-Alu: Wheeler No. 01; New Hebrides: Codrington 406; N. Am. Indian: Thompson Tales 322 n. 165, (California): Gayton and Newman 68; Africa (Zulu): Callaway 72, 105, (Kaffir): Theal 149., or T534 Conception From Blood; (Cf. †T541.1, †T563.2.) *Fb “blod” IV 47a.↩︎

See motif B751.2 Pelican Kills Young And Revives Them With Own Blood; Herbert Catalogue of Romances III 37ff. (Odo of Cheriton), Hervieux Fabulistes latins IV No. 57.↩︎

As in T82 Bath Of Blood Of Beloved To Cure Love-Sick Empress; Herbert III 212; Oesterley No. 281; Wesselski Mönchslatein 60 No. 50., or D1502.5.1 Bath In Blood Of King As Cure For Mange; (Cf. †D1500.1.9.4, †F872.3.) Irish myth: Cross., and carried through into a range of hymns using variants of the phrase “wash me in Thy precious blood.”↩︎

See D1505.8 Blood Restores Sight; (Cf. †D1003.) India: *Thompson-Balys. and its variant, D1505.8.1 Blood From Christ’s Wounds Restores Sight; Longinus. Paris Légendes du moyen âge 151.↩︎

D1503.15 Wound Healed With Own Blood; (Cf. †D1003.) Hawaii: Beckwith Myth 118.↩︎

Take the biblical book of Leviticus as an example.↩︎

As in motifs such as D766.2 Disenchantment By Application Of Blood; (Cf. †D712.4, †D712.4.1). –Type 516; Rösch FFC LXXVII 138; Fb “blod” IV 46b, 47a; Child I 337 n.; Penzer I 97; Wesselski Mönchslatein 148 No. 119. –Irish myth: Cross; Spanish: Boggs FFC XC 53 No. 400A; India: Thompson-Balys., and D712.4.1 Disenchantment By Drinking Blood; Child I 178, 337 n.; Wimberly 341.↩︎

See C913 Bloody Key As Sign Of Disobedience; (Cf. †C611, †C813.) –*Types 311, 312: BP I 404ff., or C913.1 Bloody Egg As Sign Of Disobedience; German: Grimm No. 46.↩︎

See D1318.5.2 Corpse Bleeds When Murderer Touches It; **Christensen (C. V.) Baareprøven (1900); Fb “blod” IV 47a; Knudsen (H.) En Baareprøve (Danske Studier 1932 69ff.); Von Künssberg Jahrb. f. historische Volksk. I (1925) 94, 120; Jobbé-Duval Essais de folklore juridique@2 (Paris, 1920); English: Child II 143, 146, 148, 153, IV 468a, *Baughman; North Carolina: Brown Coll. I 639; Jewish: Neuman., or D1318.5.1 Blood Springs From Murderer’s Finger When He Touches Victim; Fb “blod” IV 47a., or D1318.5.6 Blood Bubbles At Place Of Murder; Jewish: Neuman.↩︎

F991.4 Shrine Bleeds; Irish myth: Cross.↩︎

F991.4.1 Desecrated Altar Bleeds; Irish myth: Cross.↩︎

See C144 Ground Defiled By Menstrual Blood; Jewish: Neuman; India: Thompson-Balys.↩︎

Interesting that God in Leviticus is not associated with procreation and fecundity, similar to the sky-god/earth-goddess distinction, despite the obvious fertility of God in the Genesis story. Interesting also that blood in Leviticus is not associated with death or procreation but with life, and is the substance of the sacrifice at the center of the ritual act.↩︎