Tools Toward Sublimity

Why so serious?

Looking at the way Self, Nature and the Sublime are framed in Romantic-era science, it is intriguing to see how (even in fields supposedly untinged by subjectivity), the medium marinades the message. It is difficult to imagine any peer-reviewed journal today, for instance, voicing these lines from William Herschel:1

This method of viewing the heavens seems to throw them into a new kind of light. They are now seen to resemble a luxuriant garden, which contains the greatest variety of productions in different flourishing beds… we can, as it were, extend the range of our experience to an immense duration

I don’t think that the poetic or mystical strain has left scientific publication merely because of mechanization or because of a loss of faith. As science becomes more technical and complex, it requires more equipment and more people. Mystical impressions have most often been personal, individual affairs, and laying them bare would be strange and ill-fitting in a paper written by a team.

Some media are inimical to conveying certain types of messages or subjects. For instance,

| Oil | Vinegar |

|---|---|

| Syllogisms | Mysticism |

| Koans | Empirical experiments |

| Tweets | Dramatic monologues |

This is not to say that one couldn’t wrastle these subjects into these forms; but the incongruous result would read like a pomo commentary on the dilution of meaning itself (or some such well-worn theme).

I suspect that much of the erasure of the Sublime from scientific discourse following the Romantic period was due to a greater mechanization of method rather than any failure to experimentally verify the Sublime.2

More collaborators, more ground rules; including unwritten ones. Example: Genre and style guidelines provide a set of rules and allow for common language even while they impose a bland uniformity. This article about slime molds navigating mazes would be filled with exclamation marks and photos of people doing cartwheels, if not for style guidelines.

So, perhaps we don’t have to thwart an anti-religious conspiracy, but instead deal with a more practical concern. To answer the question(s):

What does a poetic sensibility look like when it seeks sublimity…

- in pastures that are ever farther from tangible experience

- which require teams of people to investigate

- and must be communicated as a collective group,

- when the fundamental unit of experience is the individual person?

Science as penitential posture

The humility woven into the scientific method might be said to have a kind of sublime ratio of self::other at its base.3 The method carries an implicit admission of the sublime baked into it, so that all theories and hypotheses are not considered ‘true’ so much as ‘not yet disproved’. A kind of via negativa, through which we know only by approaching, by almost knowing. The advance of experiment toward wonder recalls the myth of Tantalus, where the fruit of the tree recedes as soon as he grasps at it. Or perhaps more aptly that of Apollo and Daphne, in which she turns into a laurel tree as soon as Apollo (god of rationality and logic) approaches.

So what kind of tools enable one to approach the sublime? I want the answer to be something simple… like a pen, descendant of the feathery quill, with all its freight of metaphors. After all, one can only approach the infinitely weighty if one is unencumbered. Pack light, right?

In the case of Romantic-era scientists, no. And these scientists are among the best examples we have of experimental mystics.

The weight of sight

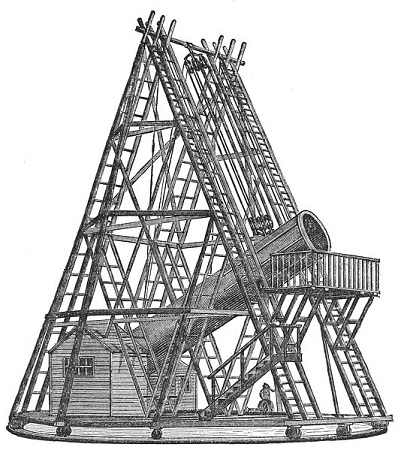

Alexander von Humboldt drags large cases of scientific instruments up Mount Chimborazo in the Peruvian Andes, and the native people of Venezuela joke about the ‘cyanometer’ which he uses to measure the blue of the sky at regular intervals. Herschel constructs gigantic lenses for his observatory in the countryside outside of London. There he spends long nights polishing them with a monkish focus on the physical medium which will re-present the stars to him.

The tools we use are far from weightless, far from natural. They become light in our hands only with use. One gains proficiency, which is to say that it gets harder to distinguish one’s own sight from the tool’s lens. Herschel comes to his notion of the universe as a garden after years (and years and years) of nightly observation. And the compactness of his metaphor should be seen as suffused with the full flavor of his process and data4.

Perhaps all tools can be oriented toward sublimity, held in the service of something greater. Being the material, form-bound creatures we are, I am beginning to think that sublimity may only be approachable through this intensive use of tools. All experience is mediated, which is not to say that reality is imprecise, but just that I am partial: I occupy a single facet, and my view is sculpted by glasses, by phrases I have lathed about my heart, by the tools I have chosen.

In poetry, for instance, perception is sculpted through pattern and repetition. It is easy to invoke the Muse, but harder to construct a song. “The pen is too light”, writes Bunting, “take a chisel to write.” Without attention to the medium in which one composes, broader claims to “Truth” are untrustworthy; vatic utterances are mere ideology if we are not attentive to their syllables, their unfolding across the substance of our days. I only ever trusted the opening celebration of Whitman’s song once I had read the lists and tallies.

To blindly abandon granular, Hydra-headed reality for some simple proxy is a constant temptation. It arises through impatience, when we begin to confuse our tools with the thing that they seek. So we get p-hacking5 in research studies, and an aversion to publishing null results6, when the finding is valued and not the search. One might note a similar cheapening of the sublime in the narrative and valuing of conversion experiences in contemporary evangelical Christians, where arrival at a dogmatic “party line” is valued at the expense of silent rigor and prayer.

Whether we celebrate the triumph of orthodoxy (the survival of icons as tools), or the triumph of science against mystery (the success of tools in mapping the material world), each celebration can become an opportunity for hubris. Entering the world must always be seen as tentative act, the tension of each doorway held in relationship to the great spaces it separates.

As he nears death, John Donne sings: “I tune the instrument here at the door, / And what I must do then, think here before.”7 His instrument is his very self, framed as merely a rehearsal for some unimaginable way of seeing up at some higher frequency. He does not succumb to listening to his own instrument as though it were the world beyond.8

All tools are infernal machines, constructed to escape our limitations and to mediate the world. These tools may have a spiritual aim (prayer ropes, prayer wheels) or a material one (astrolabe, glucometer), or both (e.g. Giordano Bruno’s ars memoria). Each is a kind of combination lock to break out of the self. Only when we fall in love with the machines themselves do we fall into what Russian spirituality calls prelest, or delusion.9

I want what is greater than all tools, all emotions or medications, all rites and rituals, all images, all maths, all interpretation, formulation, words and music. What holds these in its eye like a dust mote. And yet I must be content, that I am perhaps only a poorly calibrated device which may catch the fleeting reflection of some odd edge of earth.

My tools must show their seams and wires, must carry the coal they use for electricity. Without guile, with all the artifice they concoct and none other.

Or perhaps not a mechanization of method, but a myopic focus on method “as if the tidings were the things”, with no built in longing for the mysteries referenced.↩︎

With each discovery, the body of knowledge corresponds to an exponentially greater ignorance. That great flowering ignorance, hydra-like, sprouts seven unknowns for each fact we learn.↩︎

see Steinicke, W., & Jakiel, R. (2006). Galaxies and how to Observe Them. Springer Science & Business Media.↩︎

Head, M. L., Holman, L., Lanfear, R., Kahn, A. T., & Jennions, M. D. (2015). The extent and consequences of p-hacking in science. PLoS biology, 13(3)↩︎

Mlinarić, A., Horvat, M., & Šupak Smolčić, V. (2017). Dealing with the positive publication bias: Why you should really publish your negative results. Biochemia medica: Biochemia medica, 27(3), 1-6.↩︎

from “Hymn to God, My God, in My Sickness”, one of Donne’s last poems.↩︎

Similarly, Herbert’s “church windowes” both allow and block a view beyond, prefiguring McLuhan’s dictum that the medium is the message by a few centuries.↩︎

We might think of the myth of Icarus, so often interpreted as a warning against “flying too high”, instead as a caution against excess trust in tools. In his case, the waxen wings of Daedalus.↩︎